We had the good fortune to join in an informal discussion with the distinguished Professor of Physics who won Nobel Prize in 1957, Prof Yang Chen Ning (CN Yang).

We first started off with the question on how he chose his PhD supervisor and how he chose problems to work on in the beginning of his career. The journey began with guidance from his mathematically-trained father, and with advice from some good teachers in Tsinghua University, he went for graduate studies in the United States. He mentioned that both luck and ability play important roles in his journey. He was a theorist graduate student, so back then his ability was prized in his group who were mostly experimentalists (he had originally wanted to do experimental work). His supervisor (Edward Teller), whom he was introduced to by Enrico Fermi, managed to push him towards a theoretical path due to their earlier work together. He originally wanted to work with the biggest names of the day, but his supervisor who eventually became famous had helped him to reach where he is today.

Regarding how one should choose one's supervisors, he strongly emphasized the fact that there are two groups of supervisors and students: supervisors who want you to be very independent and exploratory (as seen in the American system), and those who would give you much advice and guidance (he gave the Chinese system as an example). There are also two types of students in this field: those who thrive under much guidance, and those who thrive when they are let loose. Which system is good depends on your character, interest and inclinations. Both have pros and cons — for example, being let loose may end up losing the focus often required for in-depth study, while too much guidance narrows your perception and creativity at times.

He stressed the fact that we should strive to find something that interests us instead of simply following what our supervisors are doing. In his opinion, our early education (right from primary school till high school) should give us some clues about our inclinations even if we may not know the exact thing we want — realizing that inclination and push towards it is one important step in doing any research or embarking on similar journeys. Doing what interests us most in this sort of work is more important and more likely to end up doing something worthwhile. At the undergraduate level we probably do not know enough — but knowing your tendencies and inclinations is often enough to guide you.

This is especially so in this generation when he was asked about the state of theoretical science today and how science today may be different from science in the past. In the past, there were possibilities for graduates to easily go very deep in one field of study, but that was also because there were fewer problems to tackle in the past. Now physics as a field of study has become much broader and thinner, and mastering one sub-field is itself much more difficult than it was back then. In a sense, doing theoretical investigations and science in general was "easier" back then when it came to scope and depth, though choices were not that many. In comparison, the broadening of physics today has made it difficult to master the subject, but at the same time it has opened up many more doors for investigation. Problems abound and the technologies are much better. This is especially so in this generation when he was asked about the state of theoretical science today and how science today may be different from science in the past. In the past, there were possibilities for graduates to easily go very deep in one field of study, but that was also because there were fewer problems to tackle in the past. Now physics as a field of study has become much broader and thinner, and mastering one sub-field is itself much more difficult than it was back then. In a sense, doing theoretical investigations and science in general was "easier" back then when it came to scope and depth, though choices were not that many. In comparison, the broadening of physics today has made it difficult to master the subject, but at the same time it has opened up many more doors for investigation. Problems abound and the technologies are much better.

The examples he gave was the development of hearing aids and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Both were sort of developed in the distant past, but only in recent years were they developed to the extent they are today. Hearing aids can be seen to have much improved, not from similar constructions but from a very distinct line of research in acoustics. MRI grew out of a simple understanding of nuclear magnetic resonance in chemistry with an ingenious twist on the homogeneity of the magnetic field generated. These indicate that even the field of medical physics has so much more lines of attack for people to study and pursue, and this richness was not nearly present in such amount back in the past. So, is this good or bad, he asked. In the end, it depends on how you look at it: one thing that is clear is that the whole environment of science in its present form is very different from that in the past.

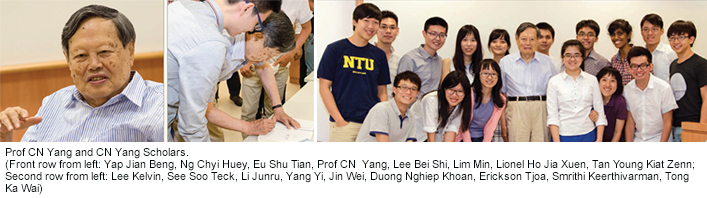

Written by:

Erickson Tjoa

Year 1 CN Yang Scholar from Physics with Second Major in Mathematical Sciences

Hear what the other CN Yang Scholars say:

During the discussion session, Professor CN Yang shared with us his own research experience. Through a series of interesting and thought-provoking stories, we are enlightened by his unique philosophy of life and research work. I was particularly amazed by one story about his refusing to publish a paper because he was not satisfied with the precision of the calculation even though his mentor had encouraged him to publish it. What I learnt from this is to always be prudent about the results so as to maintain a high standard for our work. I believe the success of Professor CN Yang is partly based on this. During the discussion session, Professor CN Yang shared with us his own research experience. Through a series of interesting and thought-provoking stories, we are enlightened by his unique philosophy of life and research work. I was particularly amazed by one story about his refusing to publish a paper because he was not satisfied with the precision of the calculation even though his mentor had encouraged him to publish it. What I learnt from this is to always be prudent about the results so as to maintain a high standard for our work. I believe the success of Professor CN Yang is partly based on this.

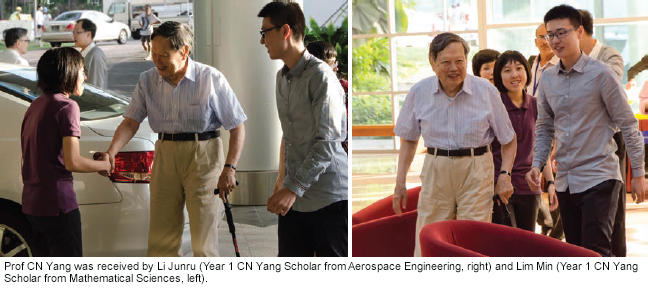

Li Junru

Year 1 CN Yang Scholar from Aerospace Engineering

When asked how he goes about identifying important or worthwhile research topics, Professor Yang replied that all of us sort of know. That is to say, we all know from young and from years of education, what interests us. And he feels that it is by cultivating this interest that interesting and important discoveries are made. He gave an example of a professor at Beijing University whose childhood interest was to collect stamps. But he realised that there are many types of stamps in the world, and if he just tried collecting all of them, it is unlikely to result in anything worthwhile.

So he started to focus his energy on collecting just one type of stamps — stamps about science. After he retired from his professorship at Beijing University, he published a book with photographs of all the stamps about science he collected and this book later won an award, and now the professor had moved on to stamps about mathematics. Professor Yang gave this as an example of how an interest cultivated and developed can result in something valuable. So he started to focus his energy on collecting just one type of stamps — stamps about science. After he retired from his professorship at Beijing University, he published a book with photographs of all the stamps about science he collected and this book later won an award, and now the professor had moved on to stamps about mathematics. Professor Yang gave this as an example of how an interest cultivated and developed can result in something valuable.

Ng Chyi Huey

Year 1 CN Yang Scholar from Mechanical Engineering with Business Minor

During the discussion, Professor CN Yang mentioned the difference between the state of the theoretical sciences then and now: back in his time, technology was not well-developed and thus limited the choices of problems scientists could investigate while currently, supercomputers and the like give modern theoretical scientists a plethora of directions to venture into. As such, he encouraged us to not be afraid of the prospect of working in the field of theoretical sciences because its range of development, contrary to what most may think, is indeed extremely large. As a student aspiring to be a theoretical physicist, on the one hand, I feel motivated to continue pursuing my dream. On the other hand, I also come to deeply admire the power of pure thought and logical reasoning that has allowed Professor CN Yang, despite the lack of modern research technology in his days, to come up with brilliant ideas that are still relevant, if not of utmost importance, nowadays in understanding how the world works. During the discussion, Professor CN Yang mentioned the difference between the state of the theoretical sciences then and now: back in his time, technology was not well-developed and thus limited the choices of problems scientists could investigate while currently, supercomputers and the like give modern theoretical scientists a plethora of directions to venture into. As such, he encouraged us to not be afraid of the prospect of working in the field of theoretical sciences because its range of development, contrary to what most may think, is indeed extremely large. As a student aspiring to be a theoretical physicist, on the one hand, I feel motivated to continue pursuing my dream. On the other hand, I also come to deeply admire the power of pure thought and logical reasoning that has allowed Professor CN Yang, despite the lack of modern research technology in his days, to come up with brilliant ideas that are still relevant, if not of utmost importance, nowadays in understanding how the world works.

Duong Nghiep Khoan

Year 1 CN Yang Scholar from Physics with Second Major in Mathematical Sciences

The informal discussion sessions with Professor CN Yang centered mainly on the topic of postgraduate studies. He responded to questions from fellow CN Yang Scholars by sharing his experience as a postgraduate student. He highlighted the difficulties that he faced in his early postgraduate days including not being able to work under Enrico Fermi on his sensitive work because of nationality restrictions and his unsuccessful attempts at experimental physics. There were a few light hearted moments when Prof Yang shared about his mistakes in doing hands-on work during his days as an experimental physicist. He mentioned a few instances in which he refused to publish his results despite encouragement from his supervisor, Edward Teller, highlighting the difference in accuracy requirements between him and Teller. When asked for advice for choosing research topics, he replied that knowledge of the field, cognizance of ongoing researches and recognition of one's interests and capabilities are crucial in selecting the right topics. Prof Yang also commented on the difference in the research landscape during his days and now: physics in his days was concentrated in a few topics while it has become much more diverse today and both scenarios have their own pros and cons for researchers. The informal discussion sessions with Professor CN Yang centered mainly on the topic of postgraduate studies. He responded to questions from fellow CN Yang Scholars by sharing his experience as a postgraduate student. He highlighted the difficulties that he faced in his early postgraduate days including not being able to work under Enrico Fermi on his sensitive work because of nationality restrictions and his unsuccessful attempts at experimental physics. There were a few light hearted moments when Prof Yang shared about his mistakes in doing hands-on work during his days as an experimental physicist. He mentioned a few instances in which he refused to publish his results despite encouragement from his supervisor, Edward Teller, highlighting the difference in accuracy requirements between him and Teller. When asked for advice for choosing research topics, he replied that knowledge of the field, cognizance of ongoing researches and recognition of one's interests and capabilities are crucial in selecting the right topics. Prof Yang also commented on the difference in the research landscape during his days and now: physics in his days was concentrated in a few topics while it has become much more diverse today and both scenarios have their own pros and cons for researchers.

Yap Jian Beng

Year 1 CN Yang Scholar from Electrical and Electronic Engineering

|