Heng Ee High School is currently the most popular secondary school in Penang, Malaysia. Every year, the School takes in nearly 800 students, and has a student body numbering approximately 3,500 — these students are the cream of the crop in the entire Penang state. However, 20 years ago, Heng Ee was an infamous underperforming school that no Chinese families was willing to send their children to. Every single day, hundreds of students used to arrive late, and were lined up to receive public canings. The turnover rate for students was so high that the school clerks were kept busy just filing paperwork for student transfer procedures.

Heng Ee High School is currently the most popular secondary school in Penang, Malaysia. Every year, the School takes in nearly 800 students, and has a student body numbering approximately 3,500 — these students are the cream of the crop in the entire Penang state. However, 20 years ago, Heng Ee was an infamous underperforming school that no Chinese families was willing to send their children to. Every single day, hundreds of students used to arrive late, and were lined up to receive public canings. The turnover rate for students was so high that the school clerks were kept busy just filing paperwork for student transfer procedures.

The pivotal figure who turned things around at Heng Ee was Mr Goh Boon Poh, who took up the post of Vice Principal at Heng Ee in 1994. He knew he had to give the school culture a complete overhaul, and acted swiftly, and with resolution — he executed public canings with a renewed severity, to the point where he injured his leading hand.

Mr Goh injected his firm beliefs in character development into the school disciplinary system. Clearly, this was very effective — before the year ended, the School gained, for the first time, 30-odd applicants who enrolled of their own accord. In 2004 he became the Principal, and for the past two decades, Heng Ee has experienced tremendous growth under Mr Goh’s guidance and leadership. The School has not only been achieving academic excellence, but has also distinguished itself in extra-curricular activities and competitions. The student body has doubled from 1,700 in 1994 to 3,550 today. Plans for an affiliated school have been laid — the new campus will be established in 2016, and looks to house another 3,000 students.

In May this year, the Chief Editor of EduNation, Ms Poon Sing Wah, attended a conference in Sabah organised by the Malaysian Conforming Secondary Schools Principals’ Council, and took the opportunity to secure an exclusive interview with Mr Goh.

At 59 years of age, Mr Goh is one of the very few top ethnic Chinese principals in Malaysia. He has won the Outstanding Principal Award in both 2007 and 2009, and this year, he was awarded the Penang State Exemplary Award and a commendation for teaching excellence by the Malaysian Ministry of Education.

He told us about the years spent remodelling the underperforming school, and how he set his reforms in motion, splitting his project into distinct phases to gradually elevate the underperforming students’ confidence and academic results, strengthen Heng Ee’s extra-curricular competencies, and finally forge a distinct and reputable school culture. After two decades of hard work, Mr Goh has transformed Heng Ee from a school with disciplinary problems and poor academic performance into both a symbol of prestige and a target of emulation in today’s education landscape.

Born to a Poor Family

Born and bred in Penang, Mr Goh was born poor. His family made a living rearing pigs and fowls, and lived in a cemetery where there was no running water or electricity. Naturally, living conditions were harsh and not conducive to studies. The family used only oil lamps that barely illuminated the immediate darkness around them, so Mr Goh did his studying outside, using whatever time and sunlight he had before dusk. But these severe conditions later proved valuable to Mr Goh in his career, as they not only strengthened his own character but also gave him an instinctive understanding of similarly underprivileged students. Even after he was married, he and his wife stayed in the old family home at the cemetery for another five years before moving out. His mother, uncle and younger brother still live there, and Mr Goh pays them frequent visits.

Mr Goh completed his high school education and pre-university courses in the prestigious Chung Ling High School in Penang, and received a Penang state scholarship to further his studies at the University of Science, Malaysia, where he majored in Mathematics and Physics. After graduating, he taught in a technical institute where the student population was largely made up of ethnic Malays for 15 years. The Malay students were generally uninterested in the sciences, so Mr Goh dedicated much of his time to helping these students raise their basic competencies. He spoke fondly of his time teaching in the technical institute. In these 15 years, he gained a deep understanding of the ethnic Malay lifestyle and ways of thought, and befriended many of his Malay teachers and students.

Mr Goh can still recall the exact date he received the rotation order to transfer to Heng Ee High School — it was on 31 December 1993. He confessed that at the time, he was less than willing to leave the technical institute where he felt very comfortably settled for Heng Ee High School with its bad reputation and seemingly endless problems. His wife was also against the transfer, and she was worried that the meek-looking Mr Goh would not be able to exert control and discipline in such a “slum” school.

What changed his opinion was the encouragement given by his former colleague and education ministry department head Mr Ismail, who told Mr Goh that he was given the job despite there being other more experienced teachers because of his proficiency in Chinese. Another friend told Mr Goh that his new posting to Heng Ee would mean an opportunity to turn the lives of many underprivileged students around. After this, Mr Goh was happy to transfer to Heng Ee.

“The moment I heard about the poor students, I felt like I had found my calling,” said Mr Goh.

The Initial Phase of Reform — Raising Discipline Standards, No Sparing of the Rod

Mr Goh officially assumed the position of Heng Ee’s Vice Principal on 1 January 1994. He started on his duties by tackling student discipline, as the School had such a poor reputation in this area. He found its disciplinary standards to be very lax — in a school of 1,700 students, more than 100 were regularly late for school. Unsatisfied with the situation, Mr Goh was determined to change this. Mr Goh officially assumed the position of Heng Ee’s Vice Principal on 1 January 1994. He started on his duties by tackling student discipline, as the School had such a poor reputation in this area. He found its disciplinary standards to be very lax — in a school of 1,700 students, more than 100 were regularly late for school. Unsatisfied with the situation, Mr Goh was determined to change this.

At the time, Heng Ee High School had only an acting principal. “This acting principal agreed with my proposal to publicly cane any student who came late,” said Mr Goh. “I remember standing at the gates with three or four other discipline staff to cane the latecomers.” The truth was that Mr Goh had no prior experience in caning a student and hadn’t the faintest idea how to handle the rod. But he stuck by his methods, and solved Heng Ee’s chronic late-coming problem with resolute hands.

Mr Goh’s efforts to raise disciplinary standards demanded more than punctuality — he was equally strict on classroom behaviour. “I would patrol the classroom corridors dozens of times every day,” he said. “If I caught anyone sleeping, I would march right in. But I would first reason with them, and see if there was any cause for corporal punishment. Interestingly, some students began bracing themselves against the wall for caning without being asked after I had scolded them. Over time, the need for such wholesale caning started to ease. But even now, whenever I catch students dozing off in class, I have no qualms about giving them a good scolding, and marching them right off to the toilet to wash their faces.”

Similar standards were expected of the appearances and uniforms of Heng Ee students. Girls with long and unkempt hair would be forced to get their hair cut short. In 1995, Mr Phuah Chor Poay was appointed as Heng Ee’s official Principal, and he was even stricter than Mr Goh in this respect — after his appointment, every Heng Ee boy had to have a crew cut. Mr Goh jokingly remarked that the girls’ short hair and the boys’ crew cuts became the “iconic images of Heng Ee”.

Mr Goh’s strictness struck fear into the hearts of all Heng Ee’s unruly students, and the School was therefore set in order within a relatively short period of time. Recalling his methods in the early years of reforming Heng Ee, Mr Goh remarked that he was extremely unpopular with the students. “Even the Founder of the School, Father Julien, thought that I was being too strict,” said Mr Goh. “Fortunately, everyone came to understand that my efforts were solely for the good of the students. I am a perfectionist, and an impatient one, at that. Even a single table out of place was enough for me to interrupt a class in order to set things straight.”

He made an analogy between Heng Ee’s reformation and the First Qin Emperor’s reformation of the writing system. “To achieve great things, one cannot waver in one’s decisions, even if they are unpopular ones,” explained Mr Goh. However, he stressed the point that ultimately caning is a very negative act.

“It was a measure taken only in desperate times,” said Mr Goh. “It was made necessary by the urgent need to reform Heng Ee’s culture.”

Fighting With Parents to Protect His Students

When Mr Goh first took up his position at Heng Ee, he had to handle more than just his students, as dealing with their parents often proved to be a knotty affair. Heng Ee was situated in the slum area where gang activities were rife, and most of its students came from the lower stratum of society. Faced with the complicated and varied backgrounds of the students and parents he encountered, Mr Goh was initially at a loss.

“I spent my younger years living in a cemetery. Naturally, I had no neighbours to speak of. After I came to Heng Ee, and witnessed the students’ domestic affairs, I came to realise how complicated a community can be.”

Perhaps it was out of fear, but students under Mr Goh’s strict teaching methods never once complained to their parents. It was the School that initiated contact with the parents, and expressed the desire to cooperate with them in taking their children in hand. Surprisingly, many of these parents started physically abusing their children on the spot.

Even till this day, Mr Goh is incensed when reminded of these irresponsible and uncaring parents. He frequently quarrelled with them over the domestic abuse his students suffered. “Because I was born very poor, I was often a target of bullying and derision. As a result, I developed a strong psychological reaction to such things. Whenever my students were bullied, even if it was by their parents, I instinctively felt the impulse to protect them. I had invited the parents to school with the intention of cooperating with them on disciplining the children. Instead, I was the one invited to witness the revolting sight of parents abusing their children. I was so angry at the time — right there and then I stood up and warned them against beating any of the students on my school grounds.”

What was most disheartening was that these parents were actually angry at the School and Mr Goh, because they felt that requests for meetings were a waste of time. They were disdainful of their own children, saying that they were hopeless and a waste of everyone’s resources. Mr Goh’s response was to challenge them to keep their children at home, if they thought educating and disciplining them was a waste of time. The parents, of course, refused.

Mr Goh offered a compromise to one such parent. He was to teach his child at least one new English word a day and in exchange, Mr Goh would allow the student to remain in school. The idea behind this contract came from Heng Ee’s students’ weakness in language. The Secondary 2 cohort could not even spell “flower”. For Mr Goh, this was indeed cause for worry.

The novel agreement sparked off an entirely new project — the daily New Word of the Day assignment for the students. Every day every student had to write at least one new English and Malay word on the blackboard. Before long, a good portion of the cohort’s language abilities started to improve. Taking the idea further, Mr Goh first introduced A Sentence A Day and then A Passage A Day assignment in all three taught language subjects — English, Chinese and Malay. After this the improvement to Heng Ee’s language standards really began to accelerate.

Heng Ee’s renewed disciplinary culture was quickly recognised by the Ministry of Education. “When inspectors from the Ministry came to visit, they were puzzled by how peaceful and quiet the school was. They actually asked me whether we were having a school break. They couldn’t believe their ears when I told them the students were having classes, and reported to the Ministry on Heng Ee’s astonishing improvement. Afterwards, they even invited the newly appointed principal, Mr Teoh Kheng Hong, to provide an account of how the School was reformed.”

The Second Phase of Reform — Promoting the Arts and Performances

Discipline alone could not possibly be the answer to all of Heng Ee’s problems; after all, the students’ emotional and family problems were complicated and deep-seated. Another challenge that presented itself was vandalism. Despite laying low and appearing docile in front of Mr Goh, many students would carry out “guerrilla” attacks after school, using hand-made catapults and firecrackers to damage school property. Mr Goh thought about this and decided that the root cause of these destructive acts lay in the students not having a proper avenue through which to channel their suppressed emotions. Discipline alone could not possibly be the answer to all of Heng Ee’s problems; after all, the students’ emotional and family problems were complicated and deep-seated. Another challenge that presented itself was vandalism. Despite laying low and appearing docile in front of Mr Goh, many students would carry out “guerrilla” attacks after school, using hand-made catapults and firecrackers to damage school property. Mr Goh thought about this and decided that the root cause of these destructive acts lay in the students not having a proper avenue through which to channel their suppressed emotions.

“The School was run like a military camp. The strengthened disciplinary measures solved the problems, by force. But this also caused a lot of unhappiness and anger among the students, and the acts of vandalism were expressions of these suppressed emotions.”

In order to create space for the release of the students’ emotions, Mr Goh introduced more extra-curricular activities. From 1996 onwards, he pushed for a greater focus on performing clubs like Chinese Orchestra, Folk Dance, Choir, the Wind Band and the Harmonica Band. Mr Goh drew this initiative from his own experiences with such extra-curricular activities back in Chung Ling High School.

“I had no money to learn music when I was younger. But I was fortunate, because Chung Ling allowed me the opportunity to join the Choir and Symphonic Band, and learn to play musical instruments for free. I think all children from poor families should have such opportunities. For my part, I try my best to let my students learn valuable skills for free, or at least at subsidised rates,” he said.

Mr Goh also knew that self-motivation is the strongest catalyst to growth and meaningful learning. Instead of trying to force the students to do well in extra-curricular activities, he tried to instil in them a sense of pride for the school by encouraging them to take part in inter-school competitions. Mr Goh ensured that such competitions were well publicised and supported his students at every single event. Furthermore, he encouraged all the students and teachers to do the same. Before long, the students were holding high the school’s competition banners and living up to the spirit of the two Chinese characters Heng (Perseverance) and Ee (Determination) in its name.

Initially, the students lacked both confidence and experience, and had attacks of stage fright when they realised their competitors were from well-known schools. To help them with this, Mr Goh took the extra step of organising internal school performances to allow the students to gain some necessary stage experience.

Although the students were not very skilled, they were happy for the chance just to be up on stage but after only two years, they were beginning to be placed in the top three positions in external competitions. In 1998, Mr Goh moved the annual school concert to Dewan Sri Pinang (a prestigious auditorium of the Penang Municipal Council), and expanded the scale of its operations, and from that moment on, the School became distinguished for its excellence in the performing arts.

The Third Phase of Reform — Raising Academic Standards and Instilling Confucianism

After Mr Goh’s efforts in improving school discipline and developing the performing clubs had paid off, Heng Ee received positive coverage in the local press. Heng Ee’s academic standards, however, remained mediocre. “Many discussions on Heng Ee’s improvements made note of how its academic standards paled in comparison to its achievements in the performing arts. These comments weighed heavily on my mind,” said Mr Goh. “We racked our brains to find a solution to Heng Ee’s mediocre academic standards. We had our New Word of the Day and A Passage A Day assignments to instil the habit of self-learning but we then decided to step up the emphasis on academic excellence, and had the teachers come back on Saturdays to provide extra tuition. Later, we even mobilised parent tutors to make sure we had enough teachers.”

Of course, Heng Ee did not achieve its academic excellence overnight — only 47 per cent of Heng Ee students passed the Malaysian Certificate of Education (equivalent to Singapore’s O level examinations) in 1999. This left an indelible mark of regret on the soon retiring Principal Mr Phuah .

“When I saw Mr Phuah’s disappointed face, I couldn’t help being affected. When he first arrived, I told him that Heng Ee’s reform was not going to be easy. He gave me a lot of encouragement and space to do what I needed to. It was a real pity that when he retired, the School was still academically mediocre. I comforted him, and reminded him of our progress, and how now, so many students were voluntarily enrolling in Heng Ee — even the 80 slots normally reserved for recommendations by board members were not enough,” Mr Goh said.

By the end of the 90s, Heng Ee had become a reputable school, but its applicants were nevertheless largely made up of average students. It was rare for the School to receive applications from students with more than four As in the Malaysian Primary School Evaluation Test, also known as the Ujian Pencapaian Sekolah Rendah (UPSR), in which there are seven examinable subjects.

Mr Goh realised that despite its excellence in extra-curricular activities and discipline, Heng Ee would never be a top school without high academic standards. In a formal meeting to discuss the issue it was Chinese teacher Mr Chan Keng Onn who made an observation that was to turn things around: what the School was lacking was a philosophy.

“When Mr Chan brought up this point, I felt immediately enlightened. Initially, I thought we were doing well in this aspect. Because Heng Ee frequently participated in competitions, I thought we had a strengthened notion of common ideals. So what had gone wrong?

“Mr Chan analysed the situation, and identified the crux of the problem. He said that the School was not imparting enough core values that would allow the students to develop the correct mindsets. Such core values would also provide a guideline for their approach in life. Thus, after further discussion, we decided that the next phase of the plan was the introduction and inculcation of Confucianism and other Chinese philosophical teachings.”

The School began by letting the students read some classic texts. However, it quickly become apparent that this method was too slow and unfocused to achieve its objectives, so Mr Chan constructed a syllabus out of ten parables, one of which being the tale of Sima Guang Za Gang, and published it as Heng Ee’s Selected Philosophical Readings. The teachers were then encouraged to vary the difficulty of the lessons according to the grades being taught.

“The content of the Philosophical Readings varies in depth, and is therefore very suitable for teaching to our students. If we force content that is too deep onto them, they would not be able to comprehend anyway,” said Mr Goh. Thus, the students learnt Confucian teachings like “do not do unto others what you do not want others to do unto you”, “a little impatience spoils great plans”, and “be kind and righteous”, and began to apply such principles to their daily lives.

Opening Week of School Used to Evaluate Performing Talent

In 2004, Mr Goh was appointed as Heng Ee’s principal. By then, Heng Ee’s pass rate for the Malaysian Certificate of Education had already reached 70 per cent. However, this number remained static in the years to follow, and Heng Ee seemed to be stuck at another impasse. Mr Goh thought hard about how to make a breakthrough, and decided that the School would start taking in as many outstanding students as possible.

Looking through the applications, Mr Goh discovered that many applicants wanted to attend the morning classes. In response, he set up a special Secondary 1 class that had lessons in the morning, and would participate in talent development training sessions in the afternoon. The purpose in doing this was to attract academically outstanding students who were also talented in dance, sports and singing. This special talent development project drew a lot of attention from top students and their parents. The parents were particularly impressed, because they knew of Mr Goh’s enthusiasm for creating opportunities for performances and talent development. Mr Goh also tailored the training sessions according to the students’ aptitudes and interests, and as a result they were groomed into school reporters, debaters and emcees respectively. Today, he has four such classes, and two of which are entirely made up of straight A students. Looking through the applications, Mr Goh discovered that many applicants wanted to attend the morning classes. In response, he set up a special Secondary 1 class that had lessons in the morning, and would participate in talent development training sessions in the afternoon. The purpose in doing this was to attract academically outstanding students who were also talented in dance, sports and singing. This special talent development project drew a lot of attention from top students and their parents. The parents were particularly impressed, because they knew of Mr Goh’s enthusiasm for creating opportunities for performances and talent development. Mr Goh also tailored the training sessions according to the students’ aptitudes and interests, and as a result they were groomed into school reporters, debaters and emcees respectively. Today, he has four such classes, and two of which are entirely made up of straight A students.

At the start of every school year, Heng Ee will identify those students who are particularly inclined towards music or performing arts. Other clubs begin seeking members only in the second week. Mr Goh justified this policy by pointing out that students talented in music and performance are not easy to find.

“After all, it takes both foundational work and aptitude to make a talent. It is not an easy combination. Some students are naturally gifted and inclined towards performance, while some are simply not meant for the stage. The art of performing entails the ability to capture and present the minutest of undertones. Thus, in our selection process, we are meticulous, and pay attention to specifics. Whether great things can be achieved depends on how one handles the details,” Mr Goh said.

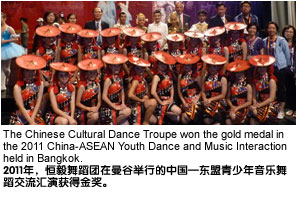

In a decade of hard work, Heng Ee’s performing arts club has regularly won awards across Malaysia, but ambitious Mr Goh feels that Heng Ee now needs to step beyond national boundaries and extend its horizons even further. In 2007, he changed the school vision to Local Roots, Global Outlook, to reflect this new goal of nurturing students who are capable of performing on the world stage. A year later, Mr Goh personally took an ensemble to compete in Beijing’s Chinese Youth Orchestra Competition. Incredibly, the team won the gold medal as well as a Best Conductor Award with its superb performance and seamless teamwork. Since then, every performing club in Heng Ee has the opportunity to compete overseas on an annual basis.

Heng Ee is also known for its large number of publications. The School produces seven of these a year in Chinese, English and Malay, including the tri-annually published, magazine-styled Heng Ee School Bulletin. Mr Goh, who had experience publishing Malay periodicals and graduation volumes during his days in Chung Ling High School, believes that such school publications are not just journals, but are also platforms that allow students to showcase their writing skills and become school journalists. Observing that the published content and presentation was often very eye-catching and inventive, Mr Goh nevertheless stressed the point that school publications should ultimately aim to guide and educate the students, and should not lose sight of this goal by pandering to popular taste.

Heng Ee has the distinction of indirectly paving the way for other schools to publish their own periodicals, and today, all conforming secondary schools in Penang have their own school bulletins.

Assigning Best Teachers to the Weakest Students

Today, Heng Ee is the most popular school in all of Penang. On average, it receives over a thousand applications a year, and these applications come in all year round. The consequence of this is that each class has an overwhelming 45 students — this is ten more than the number stipulated by the education ministry.

“Heng Ee is a Chinese conforming school, which is why I try to accept as many students as possible, so that everyone has a chance to receive a Chinese conforming education,” said Mr Goh. He explained that the 78 Chinese conforming schools in Malaysia play a key role in nurturing Chinese educators for the country. Many graduates from Chinese conforming schools further their studies in universities and major in Chinese, and go on to become Chinese teachers in secondary and primary schools all over Malaysia.

However, Mr Goh was worried that the rapid increase in the student population might cause lapses in discipline. His strategy in dealing with this possibility was to put in place a firm culture that that would influence the students’ behaviour.

“I always tell the students that it is difficult to enter Heng Ee, but it is very easy to get booted out,” said Mr Goh. When he was first appointed Principal, Mr Goh would often be on the school podium announcing the names of students who had been expelled for bad behaviour. This invariably proved an effective deterrent against disciplinary problems in the rest of the School.

Mr Goh emphasised the point that the School is firm about discipline and moral character, and has never once expelled a student for having bad results. “I often tell my teachers that our students should be treated like our own children — we do not simply give up on those with bad results,” said Mr Goh. “When I first taught in the technical institute, I employed Chung Ling’s teaching methods. But the students there complained that I was going too fast, and that’s when I realised that teachers should be student-centred in their teaching methods. Now, when my teachers tell me they have problems teaching particular students, I remind them that no effort should be spared in guiding them. It is their responsibility as a teacher.”

The teachers teaching the best class in Heng Ee have to teach the School’s weakest class as well. By teaching across a wide range of students, teachers gain a better understanding of their own responsibilities. Mr Goh routinely arranges for teachers from the best classes to teach the preparatory classes. These preparatory classes are meant for students who fared poorly in the USPR, and are conducted a year before they can officially go to Secondary 1 at Heng Ee.

Despite his many responsibilities as Heng Ee’s principal, Mr Goh still takes the time to teach at least five periods every week. He deliberately chooses to take charge of the most difficult class — this time it’s the weakest class in Secondary 3 that all his teachers complain about — in order to set an example to the school staff.

Mr Goh values flexibility in teaching methods. “If a teacher cannot adapt and change his methods, his classes will become dull and painful to the students,” said Mr Goh. He hopes that the teachers in Heng Ee do not remain content to follow the teaching guidelines set by the Ministry, but will seek to add value to their classes.

He compares teaching to making a business work — students can be considered as clients. If no clients are interested in learning from you, then your school will fail. However, when a school is enjoying patronage from many clients, its teachers must remain humble and not become conceited. Mr Goh reminds his teachers that even though Heng Ee is reputable and popular, they must always be sincere in their treatment of parents and students, as other schools are also working hard to catch up with them.

Looking to Assist the Other 77 Conforming Schools

In 2010, Mr Goh was appointed the President of the Malaysian Conforming Secondary Schools Principals’ Council. This became a platform for him to understand the other 77 conforming secondary schools. He realised that these schools shared many of the same problems as he had with Heng Ee, and he therefore wanted to help in their reformation. He also identified many good schools that had not identified a way to attract outstanding students, so Mr Goh also felt an obligation here to share his wealth of experience, and tell the other principals how he had built up Heng Ee’s reputation. One example he gave them came from the School’s early days when he would give the local press the story of any outstanding graduate who had been very unruly and disruptive when he was younger.

Mr Goh will be stepping down from his position next year. Many people think that under him Heng Ee has reached its peak, and that there will be no successor capable enough to fill his shoes. But Mr Goh disagreed, saying that Heng Ee is still far from fulfilling its potential. He stressed the point that a principal is not a civil servant, but a leader who must lead the school and chart its course. The new principal, he said, should have his own means and methods, and not just follow in his shadow. The education landscape will be vibrant and lively only when its leaders are allowed the freedom to chart new courses. The one principle Mr Goh has always lived by when managing his school is to make progress always, as to remain stagnant is to fail.

Mr Goh has no clear plan of what he wants to do after retirement. He feels no urgent need to come up with it yet. But he is sure of one thing — that no matter what he does in the future, he will continue contributing to the development and progress of the Chinese conforming schools. This interview was conducted on the day of the Model Principal Award ceremony held in Penang. Mr Goh was one of the recipients, but he sent his wife to receive the award on his behalf, as he was busy attending the Malaysian Conforming Secondary Schools Principals’ Council conference in Sabah. Admirably, he put the opportunity to interact with the other principals above his own pride in receiving the award.

Having nurtured so many talented youngsters in the 33 years of his outstanding carer as an educator, Mr Goh left us with a final piece of advice: every cog is essential in the large wheel of society. Every person has a role to play. Even average schools can play an important role in society. Even though Heng Ee was less than average in its early days, it was still able to produce a number of graduates who eventually went on to become successful and affluent professionals.

“Of course, Heng Ee in its early days had a lot fewer of these than Chung Ling, but they definitely existed,” Mr Goh said.

|