The idea of a new university was first mooted in 1996 by then Deputy Prime Minister and Minister-in-charge of higher education, Dr Tony Tan. Dr Tan was the key driver in changing the higher education landscape of Singapore, and the Singapore Management University (SMU) paved the way for other institutions like the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) and Yale-NUS College.

The first major decision made by Dr Tan for the newly established SMU was the appointment of Mr Ho Kwon Ping, Executive Chairman of Banyan Tree Holdings — a man who completed his Bachelor’s degree over nine years in three universities (Tunghai University in Taiwan, Stanford University and the University of Singapore), but who had no background in educational management — as the Chairman of the Board of Trustees.

In the months to follow, with the support of Dr Tan, Mr Ho formulated progressive and unconventional policies that sent shockwaves throughout the well-established, nearly century-old foundations of the Singapore higher education landscape. With a completely revised outlook, SMU was created to prepare Singaporeans for the advent of the 21st century.

Today, SMU has developed to become one of the best universities in Asia. It has 6 faculties and 19 research centres, and the number of students on its roll has exploded from an initial 300 to over 8,000 today.

EduNation talked to Mr Ho, Chairman of the Board of Trustees of SMU, to learn more about how the University began, how he moulded SMU into what it is today in the capacity of a change agent, and where it is headed in the new century.

Establishing a New University to Meet Rising Demand

For some time after Independence only a very small percentage of young Singaporeans went to university. But with development came an increased demand for graduates and in the 1990s twenty per cent of each cohort were getting degrees. But when even this figure started to fall short of its projections, the government was faced with a decision — should the two existing universities be made larger still, or was it time to start a third? For some time after Independence only a very small percentage of young Singaporeans went to university. But with development came an increased demand for graduates and in the 1990s twenty per cent of each cohort were getting degrees. But when even this figure started to fall short of its projections, the government was faced with a decision — should the two existing universities be made larger still, or was it time to start a third?

Linked to this question was another. What sort of university education would future Singaporeans need? Up until now, the British model of specialisation and skills in depth had been used. This had produced several generations of largely one-track professionals of the sort that any emerging economy requires. But was this model going to be the best fit for the new century?

Even before this time, Mr Ho had been critical of the narrowness of this model, and he was already convinced that the broader-based undergraduate degrees that were available in the United States were more relevant to the needs of the future. What particularly impressed him was the client customisation that they offered. The fact that graduates came away with a range of disciplines and skill sets under their belts and a degree in which they had personally shaped their final specialisation was proof enough that the products of this system would be better prepared for the changing world that lies ahead. From the university’s point of view this fluidity was also beneficial, as Mr Ho explained, “They had the liberty to merge Biology and Mechanical Engineering into Biomechanics, and Art and Computer Studies into Animation Studies. The most exciting things usually happen at the intersection of disciplines.”

But there was another reason why Mr Ho wanted Singapore’s universities to provide something different — and that was to rebut the criticisms that he felt were unfairly levelled at young Singaporeans. “I got quite fed up with so many people saying that our young people were geeky and nerdy, and that they might know everything about Maths but if you asked them a question, they couldn’t answer. Employers would also say that they would rather have a foreigner from America who had a third-rate degree than a graduate from NUS (National University of Singapore) because our students couldn’t solve problems. I didn’t think these criticisms were valid because my basic belief is that people are the same all over. It was their system that made these young Americans so desirable, so why couldn’t we implement it here?”

Being involved in the setting up of SMU therefore gave Mr Ho the chance to simultaneously change two very important perceptions: what a local undergraduate course should look like and how a local undergraduate studying it should be perceived. Reflecting on this, he said, “It allowed me to fulfil my sense of mission to bring positive changes to society, and hopefully, to change the lives of the younger generation.”

Getting Wharton On Board

But setting up a new university along these lines was not something that could be done from scratch, so Dr Tan and Mr Ho went looking for a partner, and of all the universities they visited The Wharton School seemed to promise the best pedagogical fit. Wharton, of course, was already world-famous so another tough decision had to be made.

“I think the whole council at that time was tempted to start out as Wharton and give a joint degree, or even let Wharton give the degree to gain credibility,” said Mr Ho. “But we made the decision [not to use Wharton’s name] partly because of my experience with Banyan Tree where I had learnt that if you are ever going to make it, you have to start out with your own brand, and not by being number two. So we felt that we had to bite the bullet at SMU — we would use Wharton to help us, but it was going to be an SMU degree from day one.”

The Need for Autonomy and Independence

If SMU really were to break new ground it needed to be autonomous. This was another change that had to be made to the existing set-up, as Mr Ho explained, “Before autonomy came about, the universities were run exactly like the civil service, and the university president was like the president of a statutory board. I’m glad that one of the things we did was to give the Cabinet the confidence to believe that when a university is autonomous, it doesn’t mean that it will be badly run, it can be responsible. And now, they have made all the universities autonomous.”

The Decision to Appoint an American President

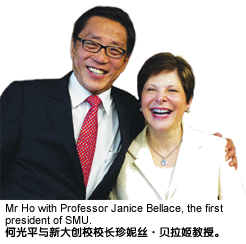

One of the biggest decisions Mr Ho made was to ask Wharton’s Deputy Dean, Professor Janice Bellace, to be the first president of the newly established SMU. This bold move raised a few eyebrows. At the time, there were many experienced and reputable local candidates who seemed to have all the right qualifications to assume this role.

“Our top priority for SMU was transformation,” said Mr Ho. “Thus, I said to get Janice because other than her philosophical background and passion for education that aligned strongly with us, everything about her was so different from us. She played a pivotal role in securing a very strong foundation for SMU in her term as the first President. Even when she was back at Wharton, she was the President of SMU, which was critical because she created a lot of connections in the United States for us. She was involved with us all along, and was willing to take sabbaticals to help us here. She would have come to Singapore to live for two years, but her father’s health was deteriorating, so she ended up coming every month.” “Our top priority for SMU was transformation,” said Mr Ho. “Thus, I said to get Janice because other than her philosophical background and passion for education that aligned strongly with us, everything about her was so different from us. She played a pivotal role in securing a very strong foundation for SMU in her term as the first President. Even when she was back at Wharton, she was the President of SMU, which was critical because she created a lot of connections in the United States for us. She was involved with us all along, and was willing to take sabbaticals to help us here. She would have come to Singapore to live for two years, but her father’s health was deteriorating, so she ended up coming every month.”

Professor Bellace set the mould for SMU presidents, and all her successors have also been internationally renowned academics, responsible both for charting SMU’s course and establishing global relations.

It is also possible that Professor Bellace’s ground-breaking appointment paved the way for other local universities to follow suit, as both Nanyang Technological University (NTU) and SUTD now have distinguished foreign academics as their presidents.

Face-to-Face Interviews with Each and Every Candidate

SMU’s mission to be an agent of change also affected the decisions made about its admissions policy. Accepting applicants on the basis of their grades alone was not going to fit the bill if the aim was to attract and create confident, articulate and engaged students. Apart from anything else, grades provide a uniform measurement, and the problem with a uniform measurement is that it can only give you a uniform result. If SMU were to be a diverse community pursuing a diversity of goals then it needed to develop an admissions policy to suit. The decision was therefore made to incorporate the much broader gauge of ability provided by the SAT as well as face-to-face interviews for all shortlisted applicants.

But even the interviews weren’t going to be typical, as Mr Ho vividly illustrated, “We have interviews where the professor puts up a problem, and the candidates discuss it with one another. By watching, we see who is likely to talk a lot, or too little, or, ideally, the person who doesn’t talk too much but says something meaningful when he or she does. Students go to the interview thinking they have to study. The whole point is that they don’t need to because we’re trying to see what kind of a person they are.” But even the interviews weren’t going to be typical, as Mr Ho vividly illustrated, “We have interviews where the professor puts up a problem, and the candidates discuss it with one another. By watching, we see who is likely to talk a lot, or too little, or, ideally, the person who doesn’t talk too much but says something meaningful when he or she does. Students go to the interview thinking they have to study. The whole point is that they don’t need to because we’re trying to see what kind of a person they are.”

Higher Tuition Fees than NUS and NTU

The decision to set its fees higher than those of the two existing universities was another creative strategy that Mr Ho brought with him from the business world. “You’re going out there with a brand nobody knows about, with a brand everybody thinks is worse than the other brands, and so the immediate reaction will be that the price should be lower. But the counterintuitive action is to set a higher price on it. ‘You might not have heard about me, but I’m pricing myself higher because I am different from the others and I am confident.’ The important thing is this: as with consumers, there are people who will always go to the popular brand no matter what. But you also have a bunch of people who want to tell their friends, ‘You’ve got this, huh? I’ve got Product X. You’ve never heard of this brand but do you know that it’s better and more expensive than yours?’ There are always people who want to be different and we wanted to get those people,” he explained.

Attracting Students and Making Them Better People

Because SMU was so different and so new, Mr Ho was aware that getting students in was going to be a challenge. As usual, though, he solved the problem by being bold and leveraging on his own marketing experience. “We decided to do it the American way,” said Mr Ho. “We went to all the junior colleges and recruited directly from there. The recruiters were our own students who went down and said, ‘Want a real fun place? Come to us.’ We wanted them to catch the eye of young people because they were saying, ‘Look, I’m confident. I can go to NUS but I’ll be different, I’ll go to SMU.’ So we got that initial batch.”

But once they were in SMU things were going to be different for these students in non-academic ways as well. Mr Ho explained, “Our students needed to see themselves as young, creative people who are going to change the world. One of the things we took from Wharton was compulsory community service. This is because it’s only when people do something that they sense the value of it, and when they do it when they’re young, it can change their lives. When our students spend a few months out in the real world, helping those who desperately need it, their eyes will open and they will see something they didn’t see when they were 16. But once they were in SMU things were going to be different for these students in non-academic ways as well. Mr Ho explained, “Our students needed to see themselves as young, creative people who are going to change the world. One of the things we took from Wharton was compulsory community service. This is because it’s only when people do something that they sense the value of it, and when they do it when they’re young, it can change their lives. When our students spend a few months out in the real world, helping those who desperately need it, their eyes will open and they will see something they didn’t see when they were 16.

“There are a lot of reasons for us to have done what we’re doing, but at the end of the day, it’s to build a better person.”

Presidents Who Stay On To Teach

SMU has continued to borrow practices and mindsets from abroad in order to change how things are done at home. One such policy is the re-hiring of presidents after they step down.

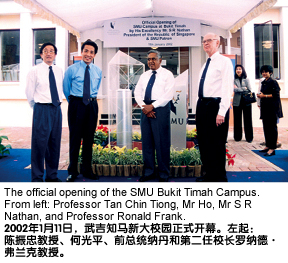

“We started it with one of our presidents, Professor Howard Hunter,” said Mr Ho. “We encouraged him to come back after he stepped down and he is a law professor for us now. And because of that, Professor Tan Chin Tiong also came back as a faculty member after his term as SUTD’s Dean.”

Mr Ho continued, “In Singapore and Chinese society in general, you cannot step down once you become a President or Dean. It’s tantamount to failure, and failures are very difficult to accept. But it is very common in the United States to become a President of a university and then step down to resume your academic career because you’re respected for your mind, not for your rank. This is how a university should operate. For example, Professor George Shultz became the Secretary of State but later went on to Stanford University where he became a professor again.”

The Need For A Residential Campus

SMU’s distinction is that it is the country’s only city university. But while this is a great attraction it is also a limitation, and in order for the students to have the full university experience that they ideally need it is important that SMU acquires a larger campus. SMU’s distinction is that it is the country’s only city university. But while this is a great attraction it is also a limitation, and in order for the students to have the full university experience that they ideally need it is important that SMU acquires a larger campus.

“NUS is now making great changes. They have the University Town, which I think is great. Students there can expect a lot of vibrancy, a lot of student entertainment and nightlife. At the same time, it is a hub for learning; it is not just a place for students to have fun. We all know that learning is not just confined to the classroom; it is a 24-hour process. Student cafes and university towns are where students talk about philosophy and argue about politics,” Mr Ho observed.

“It is regrettable that our students are missing out on these things. We understand that the land in the city is scarce and expensive, but we must still try our best to fight for more residential campus space for our students,” he added.

Introducing The Liberal Arts

SMU originally provided a business-themed curriculum only. Since then it has added a School of Law and a School of Social Sciences but despite these it still cannot be considered a comprehensive university. One of the results of this is that it cannot be ranked. SMU originally provided a business-themed curriculum only. Since then it has added a School of Law and a School of Social Sciences but despite these it still cannot be considered a comprehensive university. One of the results of this is that it cannot be ranked.

“People always ask me, ‘Why doesn’t SMU have a ranking?’ Well, there are two reasons for this. One is because we’re a bit new, and the other is that we are thought of as a specialised school.”

Therefore if SMU wants to be ranked it will have to grow. The question then is how?

One idea that is being considered is the introduction of Arts and Science faculties.

“If we have Arts and Sciences we can start to think about crafting a common curriculum. All the great universities in the United States have a very strong programme for Year One students that’s grounded in Western civilisation — Greek, Roman and Latin histories.

“Can you imagine how the game will change if SMU were to introduce a compulsory first year course in Asian civilisation to all its students? In it they would learn about Indian, Chinese and East Asian philosophies and cultures. We all say that the 21st century is the Asian century, but how many students really know the origins and linkages of Asian history and philosophy? Our students do not have the big picture.

“If our students are going to be future leaders and they don’t understand where Asia came from, they’re going to be very weak, because all the strong people in the West — whether they are scientists or leaders or artists — understand their culture. So if we were to implement this I think it would represent another important change for the better,” Mr Ho elaborated.

The Change Agent

Coming to SMU as a businessman and entrepreneur, Mr Ho was aware that it was not his academic credentials that got him the job. Coming to SMU as a businessman and entrepreneur, Mr Ho was aware that it was not his academic credentials that got him the job.

He told us, “My friends said to me, ‘What do you have that makes you stand tall before these professors and doctors? You took nine years to finish your first university degree, and you have been expelled from Stanford.’ Yes, it is true that I do not conduct research like professors do, and I do not possess a doctorate. But what I do know is that I wanted to be the agent of change, and that everyone at SMU needed to want to be agents of change. This is the secret behind SMU’s success.”

One big area of change that Mr Ho wanted to bring to bear at SMU was the whole conception of a university as a community that extended outwards into the wider community. One big area of change that Mr Ho wanted to bring to bear at SMU was the whole conception of a university as a community that extended outwards into the wider community.

“I once asked Janice to define a university in one sentence. She said, ‘A university is a place where you create and transfer knowledge.’ To transfer knowledge is to teach and to create knowledge is to conduct research. That’s fine; I think it’s very clear. A university is also a critical element in any society and it possesses and engages many stakeholders — students, parents, teachers, management, the whole community in fact. If you accept that philosophy, then all of us need to influence the university so that it doesn’t become an ivory tower, but plays a role in changing society,” he said.

After 13 years at the helm, Mr Ho is still looking to bring change but he is also very aware of what his role is as Chairman of the Board of Trustees.

“I’m very clear about where I interfere,” he said. “People have asked me if I am hands on or hands off, but I believe that in management there’s no such thing as hands on or hands off — it’s more a question of knowing when to use your hands. Because we have had so many presidents and I have been the only Chairman, I think I can set the tone for both SMU’s faculty and students in terms of what the philosophy of education should be, and of what young people should aspire towards. But I do not get involved in terms of the design of the university curriculum, the hiring of faculty members and so on.”

|