|

An Exclusive Interview with Mrs Yu-Foo Yee Shoon

Mrs Yu-Foo was the Guest-of-Honour for the Kids for Character, Character for Kids! seminar organised by NTUC Childcare and The Little Skool-House International (3 November 2007).

Mrs Yu-Foo was the Guest-of-Honour for the Kids for Character, Character for Kids! seminar organised by NTUC Childcare and The Little Skool-House International (3 November 2007).

In the middle of the 1970s, Singapore was quickly working to industrialise, and the government was actively encouraging women to join the workforce. During annual meetings of the National Trades Union Congress (NTUC) , women were already asking for childcare services from the authorities in order to allow mothers to return to the workforce with peace of mind.

Responding to these calls, the Secretary-General of NTUC Mr Devan Nair handed the heavy responsibility of setting up childcare centres to Singapore Industrial Labour Organisation (SILO)’s Mrs Yu-Foo Yee Shoon, who was its Senior Industrial Relations Officer. At that time she was one of the union’s women leaders, actively encouraging working women to sign up.

Although she had no prior experience with pre-school education, Mrs Yu-Foo, together with some colleagues, set out to establish childcare centres from scratch. In 1977 they set up the first in a detached bungalow along Kallang River. Later, when she was the Secretary of NTUC’s Women’s Programme Committee, she created a separate committee especially for childcare services. After establishing the first of SILO’s own centres she proceeded to take over the only other childcare centres that were in existence at the time, which were being run by the Department of Social Welfare.

Today, NTUC kindergartens and childcare centres have developed into one of the largest providers of childcare services in Singapore.

Mrs Yu-Foo, who has retired as a Member of Parliament and the Minister of State at the Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports, was a pioneer in Singapore childcare, and remained fully involved in the early childhood industry for more than 30 years. When interviewed by EduNation, she said, “I am very heartened to see the government realise the importance of childcare centres and early childhood education, and be willing now to invest many resources to develop this sector. I remember many years ago when a number of people felt that early childhood education was not part of formal schooling, and that the government did not need to pay too much attention to it.”

During the interview, Mrs Yu-Foo brought up a question which offers much food for thought. “How early childhood should be developed boils down to asking, ‘What kind of children do we want to groom? What kind of Singaporeans do we want?’”

Mrs Yu-Foo believes that the bringing up of Singaporeans is the collective responsibility of schools, parents, society and the government, although the roles played by parents and schools are the most crucial. “Family upbringing is of vital importance, and we need to teach values from a young age, otherwise it would be impossible to negotiate the currents of today’s extremely fast-paced world. This also has repercussions for family life. Singapore is a multi-racial society, and we therefore need to focus on multiculturalism as much as we do on ethics. To bring up children who possess both cultural literacy and the right values presents huge challenges. What is most important, though, is providing choices for Singaporeans. I feel that as long as everyone has the same goals for early childhood education, it is all right to have different options, and to seek common ground while retaining differences. At the same time, there should be certain norms, like the teaching of the acceptance and protection of a multicultural society.”

Establishing Childcare Centres

The concept of childcare was still foreign to Singaporeans in the 1970s. At that time the Department of Social Welfare ran a few childcare centres but they merely provided care. It was only after Secretary-General of Mr Nair saw that women needed this service that the job of creating comprehensive childcare facilities was given to Mrs Yu-Foo and NTUC Deputy Director of Research Professor Tom Elliott.

At that time the Industrial Workers Union had 53,000 members, and half of these were women. There was an even higher proportion of women in the textiles, electronics, food and beverage, and hospitality industries. The women representatives did not talk about pay raises, but they did bring up their concerns about childcare services and training. These were pragmatic and reasonable requests given the economic transformation of Singapore that was taking place at the time. At that time the Industrial Workers Union had 53,000 members, and half of these were women. There was an even higher proportion of women in the textiles, electronics, food and beverage, and hospitality industries. The women representatives did not talk about pay raises, but they did bring up their concerns about childcare services and training. These were pragmatic and reasonable requests given the economic transformation of Singapore that was taking place at the time.

“Back then we had neither money nor experience, so we had to do everything by ourselves. Even the buying of staples like rice was handled by members of the Industrial Workers Union. The first task of childcare centres was to ensure the safety of their charges. We had swimming pool facilities then, so of course safety was our first concern. We got in touch with doctors from clinics in the area so we could arrange for our children to get treatment immediately should they need to. If we waited for an ambulance, I’m afraid it would have taken much longer. We made full use of the strength of the community. For example, we used $100,000 donated by Shell to build a community childcare centre in Ang Mo Kio,” said Mrs Yu-Foo.

Between 1977 and 1978, NTUC Childcare also took on the ten childcare centres that were being run by the Department of Social Welfare. This brought SILO’s total number to 15. “The head of childcare services, under the purview of the Department of Social Welfare, was Ms Alice Woon, the first wife of Dr Goh Keng Swee, the former Deputy Prime Minister. She felt that what NTUC was doing was good, so she passed all the childcare centres over to us to handle,” elaborated Mrs Yu-Foo.

After ensuring that basic safety measures were in place, the next focus was the children’s mental and academic development. Mrs Yu-Foo was extremely concerned about the curriculum as well as teacher training.

“We were a group of women who knew nothing about operating even one childcare centre, let alone fifteen. Luckily, though, our team of consultants were all experts in the field. We had pediatricians from the KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, and we also had a professor from the Institute of Education to evaluate our curriculum. When we got him to conduct a longitudinal survey it showed that our childcare centres weren’t performing too badly.”

Mrs Yu-Foo was fully aware that a quality pre-school education is dependent on a base of sufficiently qualified teachers but at that time there was a serious shortage of these, so she looked abroad and negotiated with Wheelock College in Boston, USA, to train many of her first teachers. Later, the Regional Training and Resource Centre in Early Childhood Care and Education in Asia (RTRC Asia, now SEED Institute) was set up to supply a continuing pipeline of trained pre-school educators.

Actively Seeking Government Subsidies

The challenges Mrs Yu-Foo faced in the early years included a lack of money and manpower on the one hand, and a lack of public knowledge about the need for childcare centres on the other. She still remembers one Member of Parliament telling her that childcare centres would be the cause of juvenile delinquency further down the line.

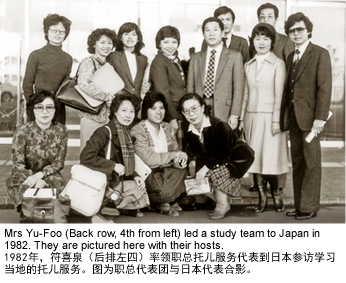

“This kind of thing made me uneasy. It was only when I visited Japan in 1982 that I regained confidence. Japan then already had 23,000 childcare centres, which had been established in the 1940s. Back then the men had to go to war, so it was down to the women to earn money. The children were therefore sent to childcare centres. At the start of the 1980s when the economy was developing rapidly, these children were already in their forties and had become a pillar of the country’s strong economic growth. This proved that there were no inherent problems with childcare centres per se, and that the most important things to get right were their mechanics, and teacher quality,” said Mrs Yu-Foo. “This kind of thing made me uneasy. It was only when I visited Japan in 1982 that I regained confidence. Japan then already had 23,000 childcare centres, which had been established in the 1940s. Back then the men had to go to war, so it was down to the women to earn money. The children were therefore sent to childcare centres. At the start of the 1980s when the economy was developing rapidly, these children were already in their forties and had become a pillar of the country’s strong economic growth. This proved that there were no inherent problems with childcare centres per se, and that the most important things to get right were their mechanics, and teacher quality,” said Mrs Yu-Foo.

Mr Nair put her in touch with two of Japan’s union leaders and the expenses for her team of five’s visit were paid for by the two Japanese trade union organisations. After she returned, NTUC Secretary-General Lim Chee Onn invited the Assistant Director (Projects), Mr Liew Heng San to help Mrs Yu-Foo draft a proposal for the Cabinet which firmly argued for the importance of working women to Singapore’s continuing economic and social development.

“Mr Lee Kuan Yew called for a meeting between us and some senior civil servants, including three Permanent Secretaries. We requested that the government subsidise childcare services, because if they didn’t it would be very hard for us to operate. However, they felt that with the generally low level of women’s salaries it would make more sense for them to stay at home and look after their children than for the government to subsidise centres that did this for them. However, we strongly opposed this view. First of all, half the men who were working then had an average salary of just $800, so their wives had to work in order to supplement this income; they were therefore unable to stay at home to look after their children. Furthermore, sending children to childcare centres would allow the children to learn and be educated, to raise their language abilities and communication skills and to develop their sporting capabilities. These are very important things for families who don’t have a very high level of education themselves,” said Mrs Yu-Foo.

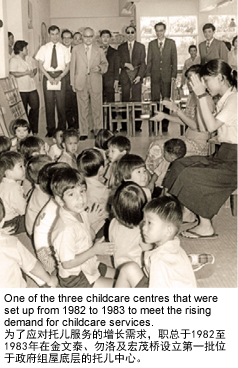

Today, the Singapore government has substantially increased childcare subsidies up to $740 per month, lightening the burdens of families whose household income falls below $7,500. This sort of policy can be traced directly back to Mrs Foo’s hard work in persuading the government to introduce a $60 per child subsidy in 1983. It was this subsidy that encouraged the setting up of further childcare centres by non-profit organisations such as the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). But even with the government subsidy, NTUC Childcare still had to hold fundraising activities to help with its costs.

From the very outset NTUC Childcare gave preferential rates to students who came from low-income families. “We would conduct means tests, and adjust our rates accordingly. The school fees we charged ranged from $60 to $300. Our financial statements were made public to let parents know that without their support, we wouldn’t be able to carry on,” added Mrs Yu-Foo.

“Mr Ong Teng Cheong, Deputy Prime Minister and Secretary General of the NTUC, saw how tough it was for us, so he told us to give up. I said we would definitely keep going, but that we needed more autonomy to do so. As a result, NTUC Childcare was incorporated in 1992. Besides providing childcare services for the general public, a subsidiary — The Little Skool-House International — was established in 1994 to cater to a different market. And as we expanded our services, we also saw our income grow.”

Early Childhood Education Has to Be Flexible

This year the government has announced a $3 billion investment in early childhood education, part of which will go to the setting up of 15 kindergartens by the Ministry of Education (MOE). Whether in terms of fund allocation or policy change, it is clear that the government is starting to realise the importance of educating young children. Said Mrs Yu-Foo, “The large subsidy for early childhood education represents a breakthrough. Today, every child in Singapore has the chance to attend a kindergarten or childcare centre. Parents can no longer say they are unable to afford the school fees for their children’s kindergarten. It can now be said that it is the fault of the parents, and not the government, if their child does not attend a kindergarten.”

Mrs Yu-Foo feels that the setting up of the 15 kindergartens by MOE serves as a reference for both parents and industry players. “I believe the MOE hopes that this will become a catalyst, and allow everyone to see the kind of curriculum that should be offered at this level in order to provide a bridge to primary school. The problem now is that there are no fixed guidelines for whether a child is ready for formal schooling at Primary 1. In Parliament, I once objected to the ‘primarification’ of kindergartens. Scholarship should not be important at this level. Children should instead learn language, art, music, physical movement, communication skills and values, and that should be sufficient. I don’t want children to attend tuition classes at such a young age, and fill up their day with these activities. I often present prizes to outstanding students, but I don’t ever see smiles on their faces. That is really sad,” said Mrs Yu-Foo.

Since there is no single best early childhood education system in the world, allowing for many varied systems is the best strategy. “I advocate flexibility for early childhood education models. The government can provide teacher training and support, but leave the rest to the people concerned. In a globalised world, we shouldn’t follow the government’s prescriptions for every single thing. In addition we have to be flexible because it’s not possible that one size fits all. The same rule goes for the workplace where employers ought to know the strengths of their employees and put the best people in the right positions.”

Mrs Yu-Foo also pushed for a one-stop integrated centre, and at the end of 2000 she established the Loving Heart Multi-Service Centre in Jurong, which brought all the community services together under one roof. “When a resident has a problem, he or she only needs to go to one place to get everything taken care of. When we do things we have to think from the perspective of the people so that our plans are compatible with their needs.”

Mrs Yu-Foo stressed the importance of approaching services from the citizens’ point of view, and used childcare centres as an illustration. “We should allow parents who need to work overtime to leave their children at a childcare centre. In Japan, I saw a childcare service that doesn’t reject any parent who approaches it, and completely fulfills the needs of parents who leave their children in their charge. The residents of one small town in Japan are required to serve community service during the week, and the childcare services are therefore extended to 10 pm. Even parents who have to work longer hours or be away for business are able to leave their children with the centres,” said Mrs Yu-Foo.

“I feel that childcare centres can consider working with grassroots organisations to employ retired women to look after the children for a few hours a day. If they’re educated they can even read stories to the children. In short the government must not leave the responsibility of the care of children solely with the mothers. The government could also encourage employers to make the workplace more family-friendly, and introduce elastic working hours for the employees. This could also yield positive results for the organisation.”

Wage Equality

While the government is pumping resources into the early childhood sector, Mrs Yu-Foo is particularly concerned about teacher calibre and working conditions. “I hope the government can directly subsidise the wages of early childhood educators and improve their working conditions. I feel that a direct subsidy of these teachers’ salaries is the most practical approach. A low salary is unable to attract good teachers. A recent announcement suggested pegging the salary of early childhood educators to nurses, and I feel this is a good starting point. I hope that in the future, we can work towards pegging the salaries of pre-school educators to primary school teachers. Hopefully in ten years’ time qualified pre-school teachers will have the same salary and benefits as regular teachers.” Mrs Yu-Foo believes that without good teachers there is no way forward for the different early childhood programmes. She would therefore like to see NTUC work with the relevant government department to come up with concrete aims and a schedule for improving teacher quality. While the government is pumping resources into the early childhood sector, Mrs Yu-Foo is particularly concerned about teacher calibre and working conditions. “I hope the government can directly subsidise the wages of early childhood educators and improve their working conditions. I feel that a direct subsidy of these teachers’ salaries is the most practical approach. A low salary is unable to attract good teachers. A recent announcement suggested pegging the salary of early childhood educators to nurses, and I feel this is a good starting point. I hope that in the future, we can work towards pegging the salaries of pre-school educators to primary school teachers. Hopefully in ten years’ time qualified pre-school teachers will have the same salary and benefits as regular teachers.” Mrs Yu-Foo believes that without good teachers there is no way forward for the different early childhood programmes. She would therefore like to see NTUC work with the relevant government department to come up with concrete aims and a schedule for improving teacher quality.

“I don’t insist on the teachers having tertiary qualifications, but they must at least be strong in languages. We could borrow resources from other countries by setting up exchange programmes for students in Europe and North America during their gap years, or for students from China who have just finished teacher training colleges. These students could come to Singapore and teach for a short period of time as English or Mandarin Chinese teachers because these are their mother tongues. The government could help to build these networks,” said Mrs Yu-Foo.

Mrs Yu-Foo has been to several big cities in China, like Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, to visit their kindergartens. She was impressed by what she saw, especially with regard to the quality of pre-school teachers. “After the reforms in China many public institutions were privatised, but Shanghai’s childcare centres remained largely public, with only one in five being privately run. Their pre-school and primary school teachers enjoy the same benefits. As long as they have been through training, teachers may choose to teach in either pre-schools or primary schools, and the government pays their salaries. This has lifted the social standing of pre-school teachers. This practice is worth learning from. Even nannies in the childcare centres, and physical education and music teachers in the kindergartens have gone through professional training.”

Mrs Yu-Foo feels that there is much more to be learnt about early childhood practices, and there is a constant need to improve. “I remember when Deputy Prime Minister Ong Teng Cheong visited our kindergartens, he said that our children looked like little ducklings when they walked, and suggested that we should offer them more physical activities. I therefore asked both Parliament and the Town Councils to provide more facilities like swimming pools and basketball courts so that this could happen. When I visited Guangzhou I found out that the kindergartens there made their children spend three hours every day outdoors. There is little of this in Singapore, because parents here tend to be overprotective.”

Donating Space for Childcare Centres

Kindergarten operators here face the problems of rising rents and a lack of suitable locations. Mrs Yu-Foo has therefore suggested that the government be more flexible in providing operators with premises for their childcare centres. One thing they can do is to formulate a policy which encourages developers to provide enough space for childcare centres, and allow operators to rent units in commercial buildings and condominiums at preferential rates.

Bearing in mind complaints from parents about the lack of childcare centres, Mrs Yu-Foo hopes the government will consider letting anchor operators have more freedom to set up centres where they are needed. Currently, the government only asks for tenders after the total number of childcare centres in any district has already been decided.

“Not having enough childcare centres is a chicken and egg problem. What are the difficulties in ramping up their numbers? If it is rent, the government could give more subsidies and encourage commercial buildings and condominiums to set up childcare centres. If it is a problem of teacher qualifications, training and working conditions, maybe we could consider employing foreign teachers?”

Mrs Yu-Foo also suggested increasing subsidies for infant care, which will not only encourage operators to provide this service but also lighten the parental burden, and incentivise more couples to have children.

There is still a lot of room for expansion in the early childhood sector in Singapore. Mrs Yu-Foo feels that Scandinavian women are the happiest because their countries ensure that the young are taken care of, the adults have good jobs and the elderly can age with dignity. “We don’t need to emulate Scandinavian countries and become a welfare state, but their childcare centres are not set up as profit-making ventures. They require the parents to volunteer and this is something we can learn from. They feel that children belong collectively to the country, to the society and should be the responsibility of everyone. Their system might not be the best but it is good as a reference,” said Mrs Yu-Foo.

The Importance of Effective Communication

Towards the end of the interview, Mrs Yu-Foo stressed that effective communication is still absolutely essential. As a Member of Parliament for 27 years, she understands fully that even when a perfect policy is introduced, it requires healthy communication channels in order that messages are effectively communicated. “I hope that the government and civil servants can improve communication with the people. Once that is in place, both parties can work together to promote development,” said Mrs Yu-Foo. In the course of establishing NTUC childcare centres and other community services, Mrs Yu-Foo has certainly encountered many obstacles, but she firmly believes that sufficient resources are readily available, and that through effective communication and coordination it is possible to harness these to build more and better platforms to serve the people.

Translated by: Lee Xiao Wen

|