The thought of failure crossed my mind a lot this week. I have been attending the inaugural 2013 Global Young Scientists Summit, or GYSS@one-north, which is modelled after the annual Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting in Germany and also the first of its kind in Asia.

The thought of failure crossed my mind a lot this week. I have been attending the inaugural 2013 Global Young Scientists Summit, or GYSS@one-north, which is modelled after the annual Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting in Germany and also the first of its kind in Asia.

It would be reasonable to hope that — after listening to 12 Nobel Laureates and other prize winners discuss their scientific breakthroughs — I would see a path, albeit long and winding, to scientific success in my own career. After all, I suspect that inspiring young scientists was the goal of the summit in the first place.

But all I could see was failure. And please do not get me wrong, I'm not the "glass half-empty" type of person. It is just that in every talk, the speakers would humorously tell us about their years of failure that in some cases lasted for decades, long before that 6 am call arrived from Stockholm bearing a message of Nobel-sized proportions.

A year of failure per Powerpoint slide, I estimated.

During the summit, Dan Shechtman, 2011 Nobel Laureate in Chemistry, recounted how fellow laureate Linus Pauling spent the last decade of his life proving that Shechtman's findings were incorrect. "There are no quasi-crystals, there are only quasi-scientists". Pauling told Shechtman, and stayed unconvinced to his death. But Shechtman remained single-minded in proving the existence of the icosahedral phase, which has now been verified to exist in nature.

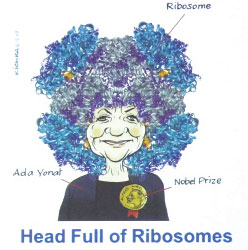

Ada Yonath tried for years to crystallize the ribosome, a large complex machine in our cells where all proteins are synthesised. Each time she tried, the ribosome crystals would melt within seconds when she attempted to view them. It was only after six years that — by pioneering the technique of cryo-crystallography — she was able to obtain the first structure of the ribosome. Considering that under five per cent of all Nobel laureates are women, it probably made winning the 2009 Nobel Prize in Chemistry even sweeter in her case.

Taken from another perspective, I'd say that these 12 laureates didn't only succeed the most, they also failed the most. Strangely, they all seemed to enjoy the iterative process of discovery.

But let's say the majority of us aren't in the category of potential Nobel nominees, are we then spared from the drudgery of failure? But let's say the majority of us aren't in the category of potential Nobel nominees, are we then spared from the drudgery of failure?

Absolutely not. Failure happens to everyone, except that those who keep on trying have the chance of escaping it occasionally, versus those who shun it at all costs. My time as a graduate student taught me that 99 per cent of all experiments are unsuccessful (in my case at least), and that aiming higher (and falling harder) was the only path to graduation.

I've also spent a lot of time promoting science careers to aspiring scientists during road shows and workshops. Rather than spend the session waxing lyrical about science, I tell them honestly that failure is part of the job description. I describe failure as a deeply misunderstood friend, and Nobel laureates as regular people who fail repeatedly while tackling the most bewildering questions out there.

However, the dogged pursuit of success is not for everyone and can even lead to unintended outcomes. Cautionary tales include Hwang Woo-suk, the Korean scientist who fraudulently claimed his team had successfully cloned the first human embryo and extracted stem cells from it. And a more recent example is Lance Armstrong, who did all he could to win the Tour de France, even at the expense of his own moral code.

That kind of intense competition is something that the Singapore education system is trying to avoid. I have been following closely the recent changes to the Ministry of Education curriculum, such as the introduction of Character and Citizenship Education (CCE) into the syllabus and also the move to withhold the scores and names of top PSLE scorers.

While I applaud the move as I recall the pressures I went through as a student, more fundamentally, students must be given the license to make mistakes at that age because failure is a better teacher than success.

Most of us may be familiar with Amy Chua, professor of law at the Yale Law School, who is also known as the "Tiger Mother". Chua insisted that her two daughters practise the piano daily, and by the time her elder daughter Sophia was 14, she had made her piano debut at Carnegie Hall in New York performing Prokofiev's Romeo and Juliet. Most of us may be familiar with Amy Chua, professor of law at the Yale Law School, who is also known as the "Tiger Mother". Chua insisted that her two daughters practise the piano daily, and by the time her elder daughter Sophia was 14, she had made her piano debut at Carnegie Hall in New York performing Prokofiev's Romeo and Juliet.

Chua's version of parenting is that one has to train hard before one can succeed, be it in music, sports, or science; and that children are not mature enough to understand the concept of delayed gratification, hence the need for constant pushing. Her methods are a tad extreme, but her words bear some truth.

Perhaps we may also need to redefine success in non-academic terms, which is why I am thrilled to see that there are now dedicated schools for aspiring ballerinas, installation artists, and bowlers.

Steve Wozniak, co-founder of Apple, once said that Singapore could not produce a company like Apple because of the dearth of creativity here.

"Where are the creative people? Where are the great artists? Where are the great musicians? Where are the great writers?" Wozniak asked in an interview with the BBC.

I think it is because failure is not acceptable in our culture that creativity is also undermined. After all, creativity brings with it a certain degree of risk. Scientific discovery is also a function of creativity, and without it, would Singapore be able to produce a Nobel laureate of its own?

As the conference wraps up on Friday, I hope that the 280 young scientists attending the event will return home with renewed confidence that it is OK to fail at something they love doing.

The article was first published in Asian Scientist Magazine on 24 January 2013.

|