Ms Loh, 62, has travelled the world and visited 30 countries. In the span of three years she slept in the wilderness, washed toilets, collected olives, had her nose tweaked by strange Iranian men, hitchhiked with heavily armed Israeli soldiers on the road, and observed countless Math lessons in almost as many different countries. Her travels armed her with valuable experiences, broadened her horizons and made her more cheerful and determined. She went on to bring daring yet confident approaches to the classroom, and introduced her students to a range of unconventional but very beneficial teaching methods.

Ms Loh, 62, has travelled the world and visited 30 countries. In the span of three years she slept in the wilderness, washed toilets, collected olives, had her nose tweaked by strange Iranian men, hitchhiked with heavily armed Israeli soldiers on the road, and observed countless Math lessons in almost as many different countries. Her travels armed her with valuable experiences, broadened her horizons and made her more cheerful and determined. She went on to bring daring yet confident approaches to the classroom, and introduced her students to a range of unconventional but very beneficial teaching methods.

In Catholic High School and The Chinese High School (now Hwa Chong Institution) she was dubbed "Goldfish", a pun on her Chinese name. She was widely known and universally loved by her students who have variously composed a song for her, written a letter to a Principal to stop her from leaving, and developed an iPhone app using her materials so that they could be accessed by all.

Q: Ms Loh, please tell us a little about yourself.

A: After I graduated from St. Nicholas Girls' School I entered the Math faculty of Nanyang University. The Math faculty of Nanyang University was famous in the 70's, and we had many outstanding teachers like Dr Teh Hoon Heng, Lee Peng Yee, Chew Kim Lin, Chen Chuan Chong, Koh Khee Meng and even an American teacher who called himself "Traitor Mike". Many of the boys from The Chinese High School forwent a place in the University of Singapore in favour of the Math faculty of Nanyang University. I was not passionate then, just a simple, naive girl who studied a lot. My grades in Math were fair, and since I liked it I decided to major in it. I was not thinking about my career options then, whether as a teacher or otherwise. My first job was also not as a teacher - I was an organising secretary in a community centre. It wasn't a bad job, and it gave me a month of youth leadership training.

Q: Did the People's Association hope to groom you as a youth leader, having put you through the training programme?

A: No. It was a mandatory programme for me and my colleagues with university qualifications because we needed to attend meetings and learn how to organise a lot of events. During meetings, we had to listen to ministers, members of parliament, members of Residents' Committees and other such important people. I remember we had to write the minutes in both English and Chinese. That was excruciating. I was posted to Cairnhill Community Centre but I wasn't there for too many months before I enrolled in the Institute of Education to become a teacher.

Q: Didn't you like being an organising secretary?

A: I did, and the job was actually a pretty good fit for my lively and energetic nature. I loved organising events and interacting with people of all ages from all walks of life. Unfortunately, the working hours of organising secretaries were long in those days.

I worked past 10 o'clock every night, and my parents were not happy about that. I respected their wishes, so when I saw that the Institute of Education was offering places for its Diploma in Education, I went to register myself. I received my diploma a year later and began teaching.

Q: Which school were you first posted to?

A: Because I foresaw that I wouldn't be staying long I decided not to enter government schools. Instead I went to St. Theresa's High, a Catholic school. Back then, I was one of the very few people who would rather have Central Provident Fund (CPF) than a pension. That was because I understood my character; I was not somebody who was going to stay in one school until retirement. I never regretted the decision to have CPF instead of a pension, because I frequently resigned.

I always felt the need to recharge myself so after any length of time in the same environment I would prefer to be carefree again. I stayed in St. Theresa's High School for four years, saved some money, then resigned in 1981 and went backpacking around the world for three years before I came back.

Q: How many countries did you travel to in those 3 years?

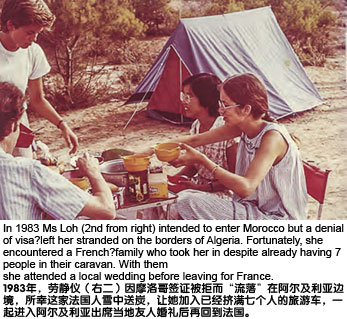

A: I toured over 30 countries. Together with a female companion the first year, I hitchhiked and travelled through South Asia -India, Nepal, Pakistan - followed by the Middle East - Turkey, Iran, Israel - and then Europe, Africa and finally North America. The time we spent at each place varied.

I worked in Israel for a community known as a kibbutz. Everybody lived together and was allocated work. No one received a salary, but food and lodging were free, and I experienced communal living. Medical bills, education and travel expenses were all paid for by the kibbutz. In return for food and board I collected olives, picked cotton, washed toilets, organised the library, had a short stint in the kitchen and generally did whatever I was tasked to do. I was free to do whatever I wanted during the weekends, and sometimes I sneaked into the universities to sit in for their lectures. Before I left, I never thought I would be gone for three years.

It was only when I was travelling that I realised how addictive it was, and that I didn't want to come back home. To fund myself, I worked as I travelled. I certainly did a lot of things from which I gained many valuable life experiences. It broadened my horizons, made me more cheerful and strengthened my determination. It also made me more confident in my ability to tackle dangerous situations.

Q: You must have had many wonderful experiences having travelled through more than 30 countries in the 1980s. Which places were most memorable for you?

A: The days I spent in Iran were very memorable. At that time Iranian men had never seen foreign women, nor were there any women out on the streets. Therefore whenever they saw one they used to try and feel her. Even though my female companion and I were covered from head to foot she still got pinched on the butt and I got my nose tweaked. When we were out in broad daylight, there would often be some Caucasian men around who would walk with us and give us protection but after 3 o'clock in the afternoon we had to return to the hostel to hide. A: The days I spent in Iran were very memorable. At that time Iranian men had never seen foreign women, nor were there any women out on the streets. Therefore whenever they saw one they used to try and feel her. Even though my female companion and I were covered from head to foot she still got pinched on the butt and I got my nose tweaked. When we were out in broad daylight, there would often be some Caucasian men around who would walk with us and give us protection but after 3 o'clock in the afternoon we had to return to the hostel to hide.

After a bit, we met a truck driver in Turkey who was going to pick up watermelons in Greece and deliver them to England. So we decided to ride with him. We passed through several European countries en route and when we reached London we were in time to witness the marriage of Prince Charles and Princess Diana.

Back in those days I was a little naive and didn't really know fear. When I was travelling along Israel's highways, I saw cannons and tanks up north. The Israeli people lined the roads with tea and cakes for their soldiers going to and from the war.

These were totally spontaneous gestures. At the border between Israel and Lebanon, I saw many returning soldiers kneeling on their home soil and kissing the ground. That was an incredibly touching experience.

Q: When did you decide to come back?

A: I had travelled through the United States and Canada, and had spent all my money. I suddenly felt that I'd seen enough and travelled enough, and that's when I decided to come back. On my travels I had visited many schools, so I looked forward to going back to teaching.

Q: Why were you visiting the schools?

A: Because at heart I was still a teacher. I had a lot of time to spare while I was backpacking and I often used it to visit schools. Whenever I arrived at a new place, I would ask the locals where the nearest schools were and off I went. I visited mainly secondary schools to observe their Math lessons, because I was a Math teacher. My requests to visit these schools and observe their lessons were never turned down. That was between 1981 and 1983 when the world was still a peaceful place. There were no acts of terrorism. My hitchhiking journey was both successful and safe. In South Africa's Port Elizabeth I visited a school set up by a Taiwanese man. He asked if I would stay on and teach, but I said I couldn't because I had yet to travel the world.

Q: Did you teach at Catholic High right after you returned from travelling the world?

A: Yes, but it was largely through coincidence. When I was in England, I met the sister of the Principal of Catholic High, Mr Tan Kiok Ngiap. She asked me to deliver a parcel for her brother. It was when I gave him the parcel that Mr Tan asked if I wanted to teach at the school. I didn't realise then that the process of being reinstated as a teacher would be so fraught with problems.

Because I had quit my job at my previous school, the Ministry of Education (MOE) refused to consider my application. I had to return to St. Theresa's High to retrieve records of my students' O level grades to prove that I was an effective teacher. In addition, I was lucky because my interviewer, Mr MacDonald, greatly admired my courage in travelling the world those three years, and said that I should go back to teaching because my experiences would surely benefit my students. I replied jokingly that it would be the MOE's loss if they did not reinstate me. I think that if someone else had interviewed me I might not have been so lucky. Even so in the three months before the ministry approved my application, I was teaching in Catholic High but receiving only a relief teacher's pay.

Q: How long were you at Catholic High?

A: I was there for nine years. Those years left many indelible memories both on me and on my students. I was extremely fortunate; I helped to produce a President's Scholar every two years. When they were interviewed, they often mentioned me. A: I was there for nine years. Those years left many indelible memories both on me and on my students. I was extremely fortunate; I helped to produce a President's Scholar every two years. When they were interviewed, they often mentioned me.

I always had high expectations of my students and was therefore critical of their work, which some students could not get used to. I often made fun of them, and they returned the favour. They liked to call me "Goldfish", which was a play on my Chinese name. They also said that I was destined to be left on the shelf. Because of my small stature they compared me to Wu Dalang, a character from the Water Margin, and suggested that I would need to bring my identity card along if I went to watch R(A) films. They attributed my killer Math questions to a woman's poisonous heart (from a Chinese proverb). Every week during assembly my students would make me get on stage to embarrass me in whatever way they could. They felt that I gave them plenty of "tough" love, and they felt no qualms returning it in kind. In fact, they often outdid me in terms of sarcastic repartee. After spending all those years engaging in such activities and exchanges it would be these memories that they held closest to their hearts.

One of my students, Ignatius Low, became the news editor of The Straits Times. He once wrote a column recounting how he, together with five other classmates, spent a fortnight composing, writing, arranging, singing and narrating the track "Angel" in a professional studio for Teachers' Day in 1988. The money needed to do all that was collected from the three classes I taught that year. Together with the tape recording, Ignatius presented me with a 13-page report on the entire process. The day I saw their performance on stage I was moved to tears.

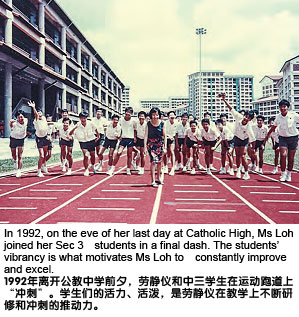

At the end of 1992 when I was about to leave Catholic High School for The Chinese High School, a class of Secondary 3 students wrote a letter to the Principal, asking him to stop me from leaving. Many students wrote to me, telling me to not stand on ceremony but to ask whenever I needed help. This really touched me.

Q: What made you decide to go to The Chinese High School (TCHS)?

A: TCHS was starting a gifted class which I wanted to teach. I was also given a Secondary 3 class. I am grateful to the Principal, Mr Tooh Fee San for his confidence in me. He gave me the opportunity not only to teach the gifted class but to plan and write its syllabus.

In CH and TCHS I was fortunate to meet many extraordinary students. They performed well because they were smart and conscientious, and the way I taught Math was rather unusual. I forced them to think and discover the answers for themselves.

Whenever my students had a query, I would never give them the answer directly. Instead, I allowed other students to try to do it. Only when the entire class had exhausted their means would I answer the question. I firmly believe that the role of a teacher is to facilitate, to help when the need arises, but not just to dispense information or issue directives.

Q: Did this also come from your classroom observations in the 3 years of travel?

A: Yes. Even though I didn't know the languages, mathematical symbols, after all, are universal. As soon as I saw what was written on the blackboard I could easily grasp the mathematical concept. Then I sat back to observe how the teachers taught those concepts and from this I learnt.

Q: Which country do you think has the best education system?

A: Israel. The high standards of Israeli schools left a deep impression on me. Even though they faced many difficulties, the people worked together cohesively to overcome setbacks. The teachers in Israel were strict, their Math lessons were pitched at a standard much higher than Singapore's, and their facilities were comprehensive. Compared to Singapore, their education system was not in the least inferior. The Jews place an inordinate amount of emphasis on education, just like the Chinese. The cultures of these two both value perseverance and thrift as well as education. If I were to distinguish between them I would say that the Jews are more creative, the Chinese more conformist. The way I kept asking questions and encouraging my students to ask questions was what I learnt from Israeli schools. I also made my students think of alternative solutions to questions they had already understood and solved. These alternative solutions might not necessarily be better, but they were a good way to promote critical thinking. Whenever I wrote mathematical supplementary exercises, I often used to include more than one method for solving the problem.

My years of travel had given me nerves of steel, and that led to daring and flexible ways of teaching. The students I taught in TCHS were mainly from the gifted class. If I felt that a certain student was ahead of his peers, I would make him sit at the back of the classroom. He would then be given harder exercises to solve by himself. For example, he would be given questions suited for students one level ahead and left alone to discover the answers for himself. I would then focus my attention on the rest of the class who weren't yet as strong. I would set aside time after class for those selected few who sat at the back to check their progress and ensure that they were coping well. If they showed that they understood the topic, they would be allowed to move on to another topic the next day.

Even though I was teaching the gifted class it still contained students with differing abilities. There were the very good, and then there were the even better ones. During lessons, if the majority of the class failed to solve a question, I would pick a student from the back to solve it. In my last batch of students I had three sat at the back whom I called the three musketeers. Now all three are in the United States or England studying Math. These students had long since learnt the habit of conscientiousness but from my class they took away an increased confidence in their abilities. One student from Catholic High said that the most important skill he picked up from me was to prove theorems or derive formulae, because I never encouraged my students to memorise these. Instead, I advocated the method of understanding by proving. This student said that when he went to the United States, he could still derive them even if he had forgotten them, which was very helpful.

Q: So instead of giving your students a fish, you've taught them how to fish so they'd have an endless supply?

A: Yes, yes. I need to thank the Principal Mr Tooh for sending me to Purdue University in the United States for a course on teaching gifted students, which greatly benefited me. As part of the course I visited a classroom where the teachers gave the students a question and left them to discuss possible solutions. The teachers didn't teach directly but instead allowed the students to engage in collaborative projects. At that time, Singapore did not yet require students to do this. It was TCHS who first introduced such a Project Work component in 1993.Other schools gradually followed suit. A: Yes, yes. I need to thank the Principal Mr Tooh for sending me to Purdue University in the United States for a course on teaching gifted students, which greatly benefited me. As part of the course I visited a classroom where the teachers gave the students a question and left them to discuss possible solutions. The teachers didn't teach directly but instead allowed the students to engage in collaborative projects. At that time, Singapore did not yet require students to do this. It was TCHS who first introduced such a Project Work component in 1993.Other schools gradually followed suit.

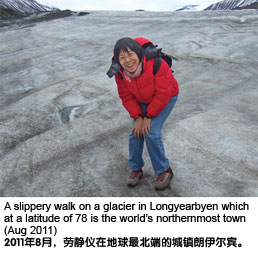

I can tell you a story that bears out the saying you used in your question. In 2011 I went to Finland and Norway, not to visit schools but to see the Midnight Sun in the Arctic Circle. However, walking along the streets I noticed how incredibly clean they were so I asked a passer-by why the city was so spotless and he said that this was the result of a good education.

What I emphasise to teachers now is to ask questions and actively encourage students to ask questions. That is very important. The only way teachers can make students think is by asking them questions. Otherwise, they will merely be passively receiving knowledge. Teachers, too, need to constantly ask if there are other answers, or other ways of solving the problem, because answers and solutions are very different things. There may only be one answer to a question, but multiple ways of solving it. It is like that old saying, "All roads lead to Rome".

I once apologised to my students for providing the wrong solution to a question. Students have to learn to acknowledge their mistakes and apologise for them. Even saints make mistakes, and we are only human. As long as we inspire students to think, creativity will follow. I find all the debates on how to "teach creativity" very strange. I believe that as long as we allow students opportunities to think, to ask, to think and to ask again, creativity will come naturally.

I never can understand why we lose our curiosity and our constant need to ask questions as adults when it is such a strong trait in us when we are children. Fortunately we are now starting to focus on early childhood education and the quality of early childhood educators again. So I hope that "question asking" and "answer seeking" can be emphasised even at this first educational stage.

Q: Not every teacher will have the chance to travel the world like you did. How else can teachers be effective?

A: We just need to show students that we truly care about them. For instance, I spent a lot of my free time in the canteen chatting with my students, talking about anything under the sun. They loved listening to my stories. My older students would tell me that even if they'd forgotten their Math, they still remembered my stories fondly. A: We just need to show students that we truly care about them. For instance, I spent a lot of my free time in the canteen chatting with my students, talking about anything under the sun. They loved listening to my stories. My older students would tell me that even if they'd forgotten their Math, they still remembered my stories fondly.

TCHS had a good practice - every day the form teacher had 20 minutes before class to chat with a student one-to-one. This was very beneficial because once the students realised you cared for them, they would naturally come to you when problems arose.

Q: Why did you leave TCHS in 2002?

A: I felt that I'd had enough of teaching. Every year I used to stress over the O level results. One month before the exams the library would extend its hours until 9 o'clock at night and everyone would study furiously in the library until then. At 9 pm when the library closed my students and I would head to the nearest MacDonald's and continue studying until 10.30 pm, when parents would arrive in droves to pick up their children. All that stress was terrible. The week before the release of the results I would have nightmares every night, dreaming that all of my students scored an F9. This scar here on my neck is where I lost a parathyroid gland for TCHS.

In 2001 I decided that I had had enough, and that it was not plausible to continue teaching. That was when I went to a monastery in France so I could speak to God. I asked him what direction my life should take, and what I experienced there led me to resign from TCHS when I returned to Singapore. I spent the following ten years concentrating on Math Olympiad training and writing educational books - textbooks as well as enrichment books for the primary level Math Olympiad. I have now written over ten books, all of which have been well received. I have had letters asking me for more books and telling me not to retire. I have also been told by parents that online materials that had cost them hundreds of dollars were not as useful as some of my books.

Q: Where are you teaching now?

A: Currently I go to different schools to coach students for the Math Olympiad, three times a week. I also travel to Indonesia and Brunei to coach.

The teachers of the schools handpick the students for me to coach for Math Olympiad competitions. My Olympiad teaching can be traced back to 1984 in Catholic High, where I was responsible for coaching students for external competitions as my extra-curricular activity.

Q: Many parents enrol their children into Math Olympiad training and tuition classes. What do you think of this phenomenon?

A: I think there are two answers to this. If the child is interested, then it is acceptable. However, if the parent only wants to send the child for training to have a shot at the best secondary schools via the Direct School Admissions (DSA), it is not. This is why when parents come to me to train their child I first ask the child if he came because he wanted to or if he was forced to. I also feel that, with a good teacher, going for these lessons will be helpful because there are no hard and fast rules regarding the syllabus. A good teacher will inspire students to think critically.

If the teacher only writes the solutions on the whiteboard for the students to copy, that would be pointless. The teacher must know how to teach, how to inspire the students and direct them to think about the questions.

Q: What has been your greatest failure in all your years of teaching?

A: That has to be the last year I spent at Catholic High. At the time, the standard of the students had deteriorated drastically. That year I was given the last class of the Express stream. There were only about five students who sat at the front of the class and paid attention; the rest of the students played. I pleaded with them and I reprimanded them; I played all my cards to no avail. I remember one student particularly; he always had one foot on a basketball, and constantly played with it while I was teaching.

I looked at them and my tears just started flowing. I had nothing left in my arsenal, no more ideas about how to reach them. This feeling of failure left me ashamed. I told myself that it was time to leave.

Q: On the whole, your students still bring you satisfaction? What has kept you going over all this time?

A: I love Math, and I love interacting with children. Teaching for me was a natural decision, especially in the 1980s, when the students in Catholic High were respectful, smart and had impeccable characters. In the 1990s when I was teaching at TCHS it was challenging and something I looked forward to because we didn't have the support of the MOE. We had to fumble along and conduct research by ourselves, but we managed to forge a path. In recent years, however, the MOE has acknowledged Hwa Chong's Gifted Programme.

On Teachers' Day, at Christmas and other special occasions, my ex-students still invite me for meals to reminisce about the old days. I attend these dinners whenever I am able. I feel that the more I interact with these young people the more I understand the world's trends and changes, and it also helps me stay young myself.

I have some students who are already in their 40s, but they still ask me to be their referee. They would have met other people of a much higher social status than me - lecturers and professors at their junior colleges and universities - but they still came back to look for their secondary school teacher. I feel very comforted by this.

Q: What advice do you have for students?

A: They should be brave and follow their dreams. I believe that people need dreams, and they should always strive to turn them into reality. No matter what they do they must be passionate about it. This will ensure that they succeed. I also tell my students to remember their roots, and to give back to society whenever they are able.

I feel that children nowadays are to be pitied - their lives revolve around the tablet or the mobile phone. They are trapped in the square box of modern gadgetry, unable to escape. They sink too much of their time into these pursuits. Recently, there was a 22-year-old university student who collapsed while playing games on his computer. He had been in my gifted class, and was one of the last students I had taught. Hearing the news about him pained me greatly. I feel that children should cultivate healthy hobbies. I remember when I was on the interview panel for the Gifted Programme in TCHS, there was a student who loved dinosaurs, and he was very interesting. He could tell us all about the different kinds of dinosaurs. There was also a student who could imitate the vocalisations of birds, which he demonstrated on the spot.

I therefore feel it is vital that we all have views, develop healthy hobbies, dare to dream and, even more importantly, have the determination and passion to follow those dreams. If we can do all this then our lives will be worthwhile.

|